History of Crete

Okay, we know that this chapter is always the most boring of all travel guides, and nobody wants to fill their head with dates and historical facts, especially when they are on holiday. At least that's how most people feel at first. As you travel, however, and hear stories, see monuments, archaeological sites, little country churches, even street names in towns that excite your curiosity, you will most likely want to take a "walk" through the history of the country.

Palaeolithic and Neolithic (33000 - 3000 BC)

Upper Palaeolithic (33000 - 8000 BC). In the final period of the Ice Age, when the level of the sea was 100-200 metres lower than it is today and Crete was joined to the Pelopponese, some palaeolithic people came to Crete in search of mammals. Deer bones have been found in the Rethimnon area which bear clear signs of having been worked by human hand - these date back to approximately 10000 BC

Mesolithic period (8000 - 7000 BC)On a mountainside between Asfendos and Kallikratis (Rethimno prefecture), a group of palaeolithic hunters decorated the cave in which they lived, with rock-wall paintings (representations of deer, weapons, etc).

Early Neolithic (7000 - 5000 BC). Groups of neolithic people, who came from the coast of Asia Minor, settled in caves in every corner of Crete. Some of these, however, were bold enough to venture out from their dark caves and to build their settlements outside, in the sunlight. The largest of these settlements (and one of the largest in the whole of the Eastern Mediterranean) was found in Knossos at exactly the same point as that where the magnificent Minoan palace was later built. Their houses were built of stakes. Their pots were very clumsy, with thick sides and decorated with white spots and linear patterns. Their weapons and their tools were simple but well-made of bone and stone. They cultivated small fields, raised small herds and knew how to weave.

Middle Neolithic (5000 - 4000 BC). As they realised that they would not be eaten by lions, more and more groups of neolithic people settled outside caves. Their houses were no longer built hugging each other, but had small yards and many small windows. Their pots were much more beautiful with thin sides and new, elegant designs. They were brownish-black in colour and had smooth surfaces and striped decorations. Their tools and weapons continued to be made of bone or stone.

Late Neolithic (4000 - 3000 BC). Neolithic settlements were especially spread out in Knossos, Phaestos and Iraklio. The foundations of a house were found in Knossos which can be regarded as the forerunner of Minoan architecture, with a spacious central room equipped with a hearth and many small rooms around it. The remains of a small circular hut were found in Phaestos, and this seems to be the forerunner of the vaulted Minoan graves. The potters of this period showed a special love of colour, and they experimented with many new shapes. They engraved decorative motifs with lines or spots onto the smooth brown, black or red surfaces of their pots, or they drew ribbons in a bright red or white colour. Their weapons and tools were still of stone or bone, but the first copper weapons appeared, probably imported and not made in Crete.

Palatial (3000 - 1100 BC)

Pre-palatial period (3000 - 2000 BC). A new people from the East came via the coast of Asia Minor and the islands of the east Aegean to Crete. They intermarried with the local population and they brought new technical knowledge, such as working in copper. A new cultural thrust was created, a preliminary period for the fantastic Minoan civilisation which will soon flourish. Seafaring and trade were developed and social classes were formed whereby rich merchants dominated and achieved political power. Their pots were much more elegant and many of these were made on a primitive potter’s wheel. Talented craftsmen made wonderful gold jewellery, seals, stone ceremonial vessels (rhytons) and works of art in ivory.

Paleopalatial period (2000 - 1700 BC). The first palaces were built in Knossos, Festos, Mallia et Zakros. Il s’agissait de luxueux palais à plusieurs étages avec des pièces lumineuses et spacieuses et de nombreux couloirs, situés autour d’une grande cour centrale, et possédaient de nombreux entrepôts, salles de travail et lieux de culte.

Around the palaces, towns were built which had no fortifications, a fact indicating that there were no internal conflicts in Crete. Industrial production (ceramics, seal-making, small sculptures) was concentrated in the palace centres and was under the direct control of the nobles. The industrial and agricultural products were exported to the main Mediterranean markets (Egypt, Cyprus, the Middle East, mainland Greece and its islands), from which the Minoans imported raw materials and merchandise (copper from Cyprus, pots and seals from Egypt, etc). In order to record their productive and commercial business, the Minoans used hieroglyphic script which remains completely indecipherable.

Neopalatial period (1700 - 1450 BC). Circa 1700 BC. A powerful earthquake shook Crete and destroyed the palaces. The Minoans found the courage to rebuild their towns and palaces from the beginning, bigger and more magnificent than the old ones and decorated with exceptional frescoes. The palace of Knossos covers an area of 22,000 square metres, of Phaestos and of Mallia 9.000 sq.m. and of Zakros 8,000 sq.m.

Circa 1600 BC. Linear A script was established. The palace secretaries kept notes on clay tablets, that no one has yet been able to decipher.

Circa 1600 BC. A powerful earthquake, which must have been related to the violent eruption of the volcano on Santorini that took place at that time, caused great destruction at the palace centres and throughout the Cretan countryside.

1600 - 1500 BC. The Golden Age of Minoan Civilisation. Weaving, ceramics, stone-craft, goldwork, seal-making and small sculpture were at their height.

The products of Cretan workshops and agricultural produce were loaded onto the spacious, seaworthy ships of the Minoan merchants and were sold throughout the Mediterranean. The wealth which accumulated gave thrust to all crafts and significantly raised the standard of living. The Minoan cities (at Gournia, Malia, Zakros and many other places) were exceptionally well-built, based on town planning, with paved roads and squares. As well as the palaces, luxury villas were built in many parts of Crete, where local noblemen and wealthy landowners lived, as were isolated farmhouses with many rooms (storerooms and workshops). The presence of the Minoans was dominant over the whole Mediterranean. They founded trading stations and colonies on the islands and in mainland Greece

Postpalatial period (1450 - 1100 BC). 1450 BC. Destruction of the second palaces by an unexplained cause (a natural disaster of great intensity or an attack by invaders). The Minoan civilisation took a great blow from which it was never to recover.

Circa 1400 BC, the Achaean colonisers of the Peloponnese became sovereign over the whole of Crete. The Palace of Knossos . Achaean colonisers from the Peloponnese became sovereign throughout Crete. The palace of Knossos was rebuilt,as was the palace of Archanes where the Achaean (Mycenaean) lords settled. Mycenaean style mansions were built in many part of Crete.

Circa 1400 BC. the Linear A script was replaced by a more developed linguistic system, the Linear B script, which is an archaic form of the Greek language. This script was deciphered in 1952, but there are still quite a lot of obscure or uncertain points.

1380 BC. Final destruction of the palace of Knossos by a powerful earthquake or by an attack by a second wave of invaders. The wonderful Minoan civilisation is wiped out completely

Circa 1200 BC. As Homer tells us, the Cretans took part in the Trojan war on the side of the other Greeks, with 80 ships and king Idomeneas as leader. This is an indication that Crete, despite the destruction of the Minoan civilisation, maintained its nautical power and had a strong presence in Mediterranean waters.

Geometric (1100 - 650 BC)

Protogeometric Period (1100 - 900 BC). Circa 1100 BC. The first Dorian colonists arrived in Crete. They were armed with swords and javelins made from a new material, iron, which was much harder than copper. The weakened locals resisted as much as they could, but without success. The Dorians became masters of the island and settled in the towns of the previous inhabitants whom they enslaved and forced to work for them. Some small groups of locals (the so-called Eteokrites, i.e. genuine Cretans) took refuge in inaccessible mountain areas in Eastern Crete and continued to live under the traditions of their Minoan ancestors.

Circa 970 BC. Protogeometric A order in ceramics. The decorators of the vases began to use compasses in order to draw straighter lines.

Geometric and Orientalising Period (900 - 650 BC). 900-800 BC . Many Doric city-states were founded such as Axos, Lato, Driros, Rizinia and Lyttos. It is estimated that the total number of cities in Crete in this period exceeds 100, but only half of these have been located. The Dorians organised their social life in accordance with the strict Doric model.

840-810 BC . Protogeometric B order in ceramics was developed in the Knossos workshops with obvious Eastern influence. The vases were decorated with bold curvilinear combinations and straight linear subjects, drawn freely by hand.

Archaic Period (650 - 500 BC)

650-600 BC . The Daedalic order, whose first traces appeared at the end of the geometric period, now reached its peak. The decorative relief works and the statues took on movement and life. This was a period of cultural flowering and prosperity in Doric Crete.

600-500 BC Invasions from Greece and Asia created terrible disorder in Crete. Bloody battles and plundering ruined the local population, crafts and trade were neglected, and the best craftsmen (like the sculptors Dipoinos and Skyllis, and the architects Chersiphron and Metagenis) left Crete and went elsewhere to look for work. The whole of the 6th century was a nightmare for Crete.

Classical period (500-330 BC)

490-480 BC During the period when the rest of the Greeks were frantically fighting against the Persian invaders, the Cretans chickened out! They put forward as the official excuse for their non-participation, the prophecy which Pythia had given them at the oracle at Delphi. When they asked her if they should participate in the war, the priestess of Apollo (who from the outset had taken the side of the Persians for financial reasons) answered plainly and clearly, without her well-known ambiguity: “don’t be childish!”.

431-404 BC During the period when the rest of the Greeks were fighting even more frantically against each other (the well-known Peloponnesian War), Crete was again totally absent because at that time it was busy fighting its own civil war: Knossos against Lyttos, Phaestos against Gortyna, Itanos against Ierapytna, Kydonia against Apollonia, Olous against Lato, a complete mess! In the end, Knossos and Gortyna predominated and the remaining cities attached themselves to these, forming two camps.

Hellenistic Period (330-67 BC)

circa 300 BCSix mountain cities in south west Crete (Elyros, Lissos, Irtakina, Tarra, Poikilassos and Syia) joined forces an formed the Koino ton Oreion (Mountainous Commonwealth) with the aim of better protecting themselves against the many enemies who threatened them.

circa 250 BC, à l’initiative de Gortyne, le Koino ton Kritaion (Commonwealth crétois) a été fondé, dans lequel les villes suivantes se sont alliées: Gortyne, Knossos, Festos, Lyttos, Rafkos, Ierapytna, Eleftherna, ApteraOn the initiative of Gortyna, the Koino ton Kritaion (Cretan Commonwealth) was founded, in which the following cities allied themselves: Gortyna, Knossos, Phaestos, Lyttos, Rafkos, Ierapytna, Eleftherna, Aptera, Polyrrinia, Syvrita, Lappa, Axos, Priansos, Allaria, Arkades, Keraia, Praesos, Lato, Viannos, Malla, Eronos, Chersonisos, Apollonia, Irtakina, Elyros, Eltynaia, Aradin, Anopolis, Istron and Tarra. It was the loosest kind of federation that created no type of obligation or bond on its members, while its general assemblies were limited to expressing good wishes!

220 BC Peace does not come about by good wishes alone. Old disputes never caome to an end and so Knossos made a sudden attack on Lytto and destroyed it, with the help of 1.000 Phokaian mercenary soldiers.

216-217 BC The Cretan cities elected the king of Macedonia, Philip V, as protector of the island. Macedonia, however, was a long way away and it seems that its protection never arrived. Civil conflict continued unabated.

210 BC War between Knossos and Gortyna.

172 BC War between Gortyna and Kydonia.

174 BC Cretan cities formed an alliance with the king of Pergamos Eumenis II.

155 BC War between Crete and Rhodes.

74 BC The Cretans finally realised the meaning of the phrase “strength in unity”. For the first time in their history, they all joined together to confront an external threat, and they achieved the incredible: in a sea-battle just off the small island of Dia (opposite Iraklio), they beat the all-powerful Roman fleet of Mark Anthony. All prisoners taken were hanged without a second thought.....

69-67 BC If the Cretans had known what would happen next, they would never have hanged those unfortunate prisoners. The Romans were enraged and sent powerful forces against Crete, led by the Roman Consul Cuidus Cecilius Metellus. After a grueling three-year war, they occupied the entire island and destroyed any Cretan cities which offered resistance. Fortunately things calmed down quickly and not only did they stop the destruction, but they also rebuilt many cities and made them more beautiful than they had been previously.

Roman Period (67 BC - 330 AD)

67 BC Crete became an independent Roman prefecture, whose capital was GortynaCrete became an independent Roman prefecture, whose capital was Gortyna, where a Roman administrator with the title of Pro-Consul was installed. Gortyna was enriched with magnificent public buildings and a long period of prosperity began.

27 BC Crete ceased to be an independent Roman prefecture and was united administratively with the Cyrenean (the Roman prefecture of North Africa, in the region of today’s Libya).

58 AD St. Paul himself ordained his disciple Tito as first Bishop of Crete, with the seat of his bishopric in Gortyna.

249-251. During the reign of Emperor Decius, the first serious persecutions of Christians in Crete took place. In Gortyna, ten young Christian died a martyr’s death - the so-called Holy Ten.

Circa 295. The Emperor Diocletian made an administrative reorganisation of the Roman empire. The prefecture of Crete was taken out of the Cyrenian and included in the Administration of Mysia (a Roman prefecture in the Balkans).

300-330 The cartographers of this period must have gone crazy with scribing and rubbing out, as the borders of the dominions of the Roman Empire changed almost every month due to the continuous clashes between those claiming power (in one particular year, there were seven emperors simultaneously, each one claiming his own vital space!). The final triumph out of all this confusion belonged to the Emperor Constantine the Great, who abandoned Rome and built the new capital of his state, the splendid Constantinople, on the site of an old Megaran colony, Byzantium (after which it was- wrongly- named the Byzantine Empire). As for Crete, it followed developments without participating.

First Byzantine period (330-824)

337 After the death of Constantine the Great, his three sons divided the Roman Empire into three. The youngest of the three brothers, the then underage Constantas, got Crete together with the Administration of Illyrium (which included the whole of mainland Greece), Italy and North Africa. The eldest brother, Constantinos II, got the West (i.e. the Administrations of Spain, France and Britain). The middle brother, Constantios II, got the East (i.e. Thrace, Asia, the Pontus and Egypt).

340 The eldest brother, Constantinos II, thought that it would not be difficult to push out his younger brother, Constantas, and take his state from him. But the young man tricked him, killed him and took his state from him instead (as we say, “the bites bit”!). So, on the map at that time remain the East Roman Empire and the West Roman Empire (to which Crete belonged)

395 The Emperor Theodosius I annexed East Illyrium to the east Roman State and so Crete joined its fortune to what later became the Byzantium Empire.

Circa 670. The Arab pirate Bavias conquered and plundered many Cretan towns, giving a foretaste of the harshness of his race which would soon ruin the island.

823 The Arabs who had conquered Spain were being increasingly driven into a corner by the Spanish and realised that they must soon look for new land to absorb. After extensive research, an Arab patrol of 20 ships, led by the cruel Abu Omar Haps, swallowed up the neglected and weakened Crete.

Arab conquest (824-961)

824 A year after the first landing, the rest of the Arabs arrived with 40 ships. They made a sweeping attack on the interior of the island, leaving in their wake thousands of dead Cretans, ruins and burnt land. The land where the refined Minoan civilisation had once flowered, sank into the deepest darkness in its history, conquered by the ruthless Arabs. They made their capital at Chandaka (today’s Iraklio), an insignificant settlement in the centre of the north coast which was once the port of Knossos and which now became the biggest base for pirate attacks and the centre of the slave trade in all the Mediterranean.

825 Alarmed, Constantinople immediately made the first attempt to free Crete on the orders of Emperor Michael II and his generals, Foteinos and Damianos, but without success.

826 The Byzantines made a second, more serious attempt with 70 ships and 23,000 men and managed to take Chandaka. The Arabs retreated to the interior of the island and reformed themselves while the stupid Byzantine soldiers were celebrating with all-right drunken orgies. One evening, the Arabs suddenly attacked the unguarded city and murdered any Byzantines who did not have time to run away. Constantinople took many decades to get over this shock...

902 The Emperor Leon VI the Wise, wisely judged that the time had come to relieve the Mediterranean from the Arab pirates. He organised an expeditionary force of 180 ships and entrusted the leadership to Admiral Imerios who, however, proved to be deeply ignorant on matters of strategy: the Arabs went to meet him at Limnos, sank his fleet and killed most of his soldiers.

949 The Emperor Constantine VII made the fourth attempt to free Crete, but his general, Constantinos Gogylios, failed miserably.

960-961 The Emperor Romanos II made the freeing of Crete a priority matter and entrusted the organisation and leadership of the new campaign to his best general, Nikiforos Fokas.

Fokas made careful preparations, determined to crush the Arabs; he armed 3,300 ships, 2,000 of which had special launchers for the new superweapon of the time, liquid fire (a mixture of petrol and other ingredients-a Byzantine invention). He landed outside Chandaka and fought the first decisive battle with the Arabs who had lined up outside the city walls. When the dust of battle settled, the ground was littered with 40,000 dead Arabs, while those who could, took refuge inside the walls. The Byzantines immediately began the siege, punishing the previous barbarity of the Arabs with the revenge they thought they deserved - they beheaded the dead and the prisoners of war and stuck the heads on stakes around the walls. They shot the left-over heads from their catapults over the walls, into the city. After they had shot over several thousand heads, the morale of the besieged men was shattered and the Byzantines entered Chandaka. They added another 160,000 to the mountain of chopped-off Arab heads and after that, the Arabs literally did not again raise their heads...

Second Byzantine period (961-1204)

962-968 Nikiforos Fokas tried to move the capital of Crete to a safer place in the interior, and began to build a fortress which he called Temenos. After he was recalled to Constantinople, the inhabitants returned to the ruined Chandaka and rebuilt it.

1082 The Emperor Alexios II (Komninos) “inoculated” Crete with 12 Byzantine noble families, among whom was his son, Isaakios. This was the seed from which sprang the local Cretan aristocracy that quickly took ownership of large areas of fertile land, accumulated great economic and political power and played a leading part in the social and political life of Crete, even under Venetian rule.

1203 The Byzantine prince, Alexios, in his attempt to reinstate on the throne his deposed father, Isaakios II Angelos, gave Crete away to the Venetian leader of the Crusaders, Boniface Monferatico, in order to secure his support.

Venetian rule (1204-1669)

1204 Boniface did not know what to do with Crete and he sold it to the Doge of Venice, Enrico Dandolo, for 5,000 gold ducats, i.e. for a pittance!

1206 Before the Venetians had time to settle themselves in Crete, their vindictive enemies the Genoans, led by the archpirate Enrico Pescatore, conquered a large part of the island and had time to build 14 fortresses to secure the conquered land. But their effort was in vain.

1206-1217 Venetian-Genoan war on foreign soil (in Crete). The Venetians won and threw the Genoans out of the island. The kingdom of Crete was founded (Regnio di Candia) with Chandaka as the capital, where the administrator of the island, who had the title of Duke, was installed. The island was divided into six areas (sestieri) that were given to Venetian feudal lords to exploit. The pre- existing Cretan aristocracy developed alongside the Venetian aristocracy.

1211 The Aghiostephanites Revolution, the first revolution by the Cretan nobles (specifically by the Aghiostephanites family with the support of the people, of course) against the Venetians. The Duke of Crete, Jacomo Tiepolo, could not suppress it and asked for the help of his colleague, Marco Sanoudo, the Duke of Naxos, promising him a handsome reward. Sanoudo, after much trouble and sacrifice, managed to put down the revolution, but Tiepolo refused to give him the agreed reward. So Sanoudo got angry, fought with the Cretans and captured Chandaka, Tiepolo had time to escape, disguised as a woman. The Venetian motherland then intervened, made a reconciliation between them, and Sanoudo returned to Naxos. It is not known whether Tiepolo continued to wear women’s clothes.

1212 First large-scale colonisation of Crete by the Venetians. Venetian nobles settled on the island with their families. They selected the most fertile pieces of land and shared them out between themselves. The now landless locals worked without wages as serfs for the Venetian lords on the land which had previously been theirs.

1217-1219 The Skordilides and Melissinos Revolution. These Cretan Lords had great support from the people and managed to dominate the whole of West Crete. The Duke of Crete, Domenico Delfino, was forced to give them land and privileges.

1222 The second batch of Venetian colonisers arrived in Crete and grabbed even more land. The noble Melissinos family considered that they had suffered damage and rose in revolution for the second time (not on its own, of course, but with the support of the people!). The Duke of Crete, Paolo Corino, came to a compromise with them and granted them new privileges.

1228-1236 The more you have, the more you want, and the greedy Melissinos again incited the Skordilides family and two other noble Cretan families (the Dracontopoulos and Arkoleos families) to revolution. The Venetian Duke was again unable to face them and, without much delay, he granted new privileges and feudal lands to the Cretan nobles in an attempt to avoid total defeat. So the Skordilidos and Melissinos families (who didn’t care about freeing Crete and were interested only in lining their own pockets) betrayed the cause, whilst the Drakondopoulos family, who were patriots, continued on their own, but they were decimated and left the island.

1252 There was room for even more. The third batch of Venetian colonists came to Crete and grabbed whatever was left. More than 10.000 Venetian colonists in total (from the capture of the island to that date) had left their cramped, damp houses in Venice to settle in sunny, spacious Crete, mixed up with around 150.000 Cretans.

1261 After the recapturing of Constantinople, the Byzantine Emperor, Michael VIII, tried to pick up the pieces of the Byzantine empire, starting with Crete. He incited the Cretan Lords (the Chortatsides, Psaromiligos and Melissinos families) to revolution, but they confused the national and their personal interests and made a mess of it. The Venetians exploited their differences, immediately satisfied their personal demands (with grants of land and privileges) and things ended there.

1272-1278 The Chortatsides Revolution, with a genuine rational character this time. The rebels routed the Venetians and they laid siege to them at Chandaka. The man who saved the Venetians from certain defeat was a miserable traitor, the Cretan Lord Alexios Kallergis, who acted simply and solely for reasons of personal opposition to the other Cretan Lords. As soon as they recovered from the shock, the Venetians carried out horrible acts of revenge to set an example.

1282-1299 The Kallergis Revolution. It seems that the exchange made by the Venetians to Alexios Kallergis for his services did not satisfy him, so he made an unprecedented revolution! Indeed, it ended up in defeat for the Venetians and in the “Kallergis Treaty”, which granted very large areas of land and the title of Venetian Noble to the all powerful Cretan Lord, Alexios Kallergis!

1319 Revolution at Sfakia, which was put down by the Venetians with the help of their friend Alexios Kallergis.

1330 Revolution by the Magarites family, which was also suppressed by the Venetians, with the help of George Kallergis, the son of Alexios.

1341-1347 Revolution by Leon Kallergis (almost the only Kallergis not to side with the Venetians), who stirred up other noble families such as the Psaromilirgos, Skordilides, Sevastos and Melissinos families. The Venetians put down this revolution too and took revenge on all the instigators and those under suspicion, with the most horrible tortures and the most barbaric executions. Alexios Kallergis, the grandson of the previous Alexios Kallergis, was an important helper and ally of the Venetians. As you can see, betrayal was a traditional sport in the wealthy Kallergis family.

1363-1366 The Saint Titos Revolution. For the first (and last) time, Venetian and Cretan nobles joined forces to rebel against the Venetian motherland with the aim of making Crete an autonomous Republic and for them to pocket the enormous tax revenues instead of sending them to Venice. The instigators of the revolution, which succeeded temporarily in its aim, were the Venetian nobles Gradenigo and Venieri, and the noble Cretan Kallergis family. This was too serious and enraged Venice, which immediately sent huge forces, suppressed the revolution and beheaded the instigators.

1415 One of the first travellers to visit Crete, the Italian Cristoforo Buondelmonti, wrote his impressions in a travel book which became the Bible of later travellers to Crete.

1508 A terrible earthquake almost completely destroyed Chandaka and killed thousands of its inhabitants.

1527 The Revolution of George Kandanoleos, or Lyssogiorgis, which the Venetians had little difficulty in suppressing. The instigators were beheaded, while the whole of the noble Kontos family (around 1,100 people), who were thought to be on friendly terms with the Kandanoleos family, were exiled.

1538 Cherentin Barbarosa, the most fearful pirate who ever operated in Mediterranean waters and arch-admiral of the Turkish fleet, attacked Crete. He was unable however to capture Chania, Rethimno and Chandaka, and he plundered the isolated Sitia and the whole of Lasithi.

1570 The Turks, the new power starting to dominate the Aegean, conquered Cyprus (as you can see, the Cypriots have old accounts to settle with the Turks). Their next target was Crete, which the Venetians were no longer in a position to protect effectively.

1577-1614 The Cretan painter, Dominicos Theotokopoulos known as El Greco, lived and worked in Toledo, Spain.

1550-1650 Period of peak intellectual achievement in Crete. Both, scholars and ordinary Cretans wrote pastoral poems, tragedies, and comedies, and this art reached its zenith with the narrative love poems Erofili by Chortatzis and Erotokritos by Vicenzo Kornaros, written in the language of the common people.

1644 A Turkish ship carrying pilgrims on their way to Mecca was arrested in the open sea off the coast of Crete, and the Turks used this as the official excuse they were looking for the invade Crete. The Turks accused the Venetians of harbouring Cretan pirates and they prepared for one of the bigger military operations in their history.

The Turks attacked Crete with 400 ships and 50.000 soldiers. They landed near Kasteli Kissamou and laid siege to Chania. After a siege of two months, they captured the city.The leader of the Turks was Yousouf Pasha and the defender of Chania was the Venetian general Kornaro.

1646 Rethimno fell into the hands of the Turks after a siege of 45 days

1648 The whole of Crete had now been captured by the Turks, except for the well-fortified Chandaka. The Turks gathered all their forces and began the siege of the capital. The Venetians together with the Greeks proved themselves to be hard nuts to crack and defended themselves effectively for 21 years, the longest and hardest siege of a castle in history.

1669 Chandaka fell into the hands of the Turks, who had paid the heavy toll of 108,000 dead for their conquest. But the besieged too were in mourning for their approximately 30,000 victims. Those who were left had a time-limit of 12 days to abandon Chandaka, in accordance with the terms of surrender. The Turkish military commander during the final years of the siege was the Vizier Ahmed Kioprouli, and the leader of the defenders of Chandaka was the Venetian Fransisco Morozini.

Turkish rule (1669-1898)

1671 The Turks took a census of the population in order to impose their well-known poll-taxes and levies. At this time, it was found that around 60.000 Christians and 30.000 Moslems inhabited Crete.

1691 The Turks captured the fortress of Gramvousa which until then the Venetians had maintained control of.

1692 The Venetians sent their admiral, Domenico Motsenigo to Crete, stirred up the Cretans and attacked the Turks at Chania. The Turks defended themselves effectively and afterwards inflicted exemplary reprisals at the expense of the locals, naturally, and not of the Venetians, who got into their ships and sailed away.

1714 The Turks captured the fortress of Souda which was held by the Venetians.

1715 The Turks captured the fortress of Spinaloga, the last bastion of the Venetians in Crete, and they were at last absolute rulers of Crete.

1770 – 1771 The Daskaloyianni Revolution. The Russians, who had a dispute with the Turks, persuaded the Sfakians to rebel against the Turks, promising that they would help them. The help, however, never came and the 2,000 rebelling Sfakians, led by the legendary Yiannis Vlachos, or Daskaloyiannis, found themselves face to face with 15,000 better equipped Turks. After a few temporary successes on the part of the Sfakians, the Turks fought back and cornered them at Sfakia. They set fire to the villages and the property of the rebels, killed and captured many in the battles and, finally, Daskaloyiannis surrendered. The Turks again demonstrated their cruelty - they skinned Daskaloyiannis alive in the central square of Iraklio...

1821 The great Greek revolution which broke out in Mainland Greece spread to Crete, the nucleus again being the inaccessible Sfakia. The Turks responded with plunder and mass slaughter (like the slaughter of 800 Christians at Iraklio) but the Cretan rebels managed to strike some powerful blows on the occupying forces in all corners of the island - in the battles of Therisos, Lakkon, Rethimno and elsewhere, the Turkish army suffered great losses. The Cretan chieftains, however, did not manage to avoid internal disputes and so they asked mainland Greece to send someone to undertake the general command. The leader of the Greek revolution Dimitrios Ypsilantis, sent Michael Afentoulief to Crete who did what he could to coordinate and organise the revolution in Crete. But the Cretans were stubborn and couldn’t conquer their egotism. If they had had a little more accord, they would have thrown the Turks into the sea much earlier.

1822 The Sultan saw that he could not manage things on his own and he asked Mehmet Ali of Egypt for help. He landed at Crete with a very big Egyptian army and the scales turned again on the side of the Moslems who, after every victory, plundered, burned and ravaged everything before them. The morale of the Cretans was gradually lowered as they saw their country turning to ashes and ruins

1823 Afentoulief was deposed and Emmanuel Tombazis became leader. In a decisive battle on the plain of Mesara, the Turko-Egyptian army beat the Cretans. A few months later, Tombazis left Crete and the revolution was effectively over.

1825 A band of Cretan rebels came from the Peloponnese and captured the fortress of Gramvousa. The revolution rekindled. Gramvoussa. The revolution has been revived.

1825-1828 The Gramvousa Revolution. With the fortress of Gramvousa as the centre of operations and under the direction of the “Council of Crete”, whose chairman was the Warrior Vassilis Chalis, the revolution spread in west Crete.

1828 The Battle of Frangokastelo. The brave warrior from Epirus, Hatzimichalis Dalianis tried but could not beat the more numerous army of Mustafa Pasha.

Dalianis himself was killed in battle, with the greater part of his army. But Mustafa also sustained a sudden attack by the Sfakian rebels during his return to Iraklio, and he suffered great losses.

1828 The first Governor of Greece, Ioannis Kapodistrias, realised that Crete was a lost cause and ordered the Cretans to stop fighting. The Cretans felt betrayed but they did not abandon their attempt to free themselves from the Turks and to be included in the newly formed Greek state.

1830 Despite the hard struggle the Cretans had put up all these years and the rivers of blood that had been shed, the London Protocol, which was the first official international recognition of the Greek state, left Crete out of the Greek borders....

1830 -1840 Egyptian Occupation of Crete. The Sultan Mahmut IV ceded the whole of Crete to the Egyptian viceroy, Mohammed Ali in recompense for Egypt’s help in putting down the Cretan revolution. In the beginning, the Egyptians showed themselves to be better masters than the Turks; they granted a general amnesty, asked the people to return to work, opened the schools and carried out many infrastructure works (roads, bridges, harbours, etc.), although at the expense of the people of course.

1833 The Mournies Revolution. Around 7.000 unarmed Cretans gathered at the village of Mournies to protest against the very heavy taxation, and in parallel sent a written protest to the Great Powers (England, France and Russia). The Egyptians showed their true face: they arrested the instigators and hanged them from the village trees, while they terrorised the inhabitants with similar acts throughout Crete.

1834 The English traveller Robert Pashley travelled for seven months through the whole of Crete and managed to locate and identify more positions of ancient Cretan cities than any previous investigator. His two-volume work “Travels in Crete”, published in 1837, is one of the most important travel books ever written about Crete.

1840 The Egyptian Governor of Crete, Mohammed Ali, made a mess of his war operations in Syria. The Great Powers intervened and in the Treaty of London, Crete was taken away from the Egyptians and given back to the Sultan.

1841 The Chereti and Vasilogiorgi Revolution, which took its name from its two chieftains. Mustafa Pasha quickly crushed it and a new wave of violence broke out against the Christians.

1856 The Sultan realised that he could not continue being so tyrannical over his subjects and issued a firman (writ), the famous Hati Houmayioun, whereby he granted them important rights such as religious freedom, personal freedom, protection of property, etc.

1858 The firman mentioned above never arrived in Crete, so the Mavroyeni Movement arose. Around 5.000 unarmed Cretans gathered in Chania to protest and to send a written report to the Sultan and to the Great Powers. The Turks took a conciliatory stance, obviously fearing an international outcry, and promised to grant the Cretans the rights laid down in the Sultan’s writ.

1865 The English admiral T.A.B. Spratt, who came to map the Cretan coast, took the opportunity to make an extended tour in the interior as well, and to write a very interesting travel book.

1866-1869 The Great Cretan Revolution. The Turks continued, as was expected, to violate the Christians’ statutory rights, imposing new taxes. The Cretans rose up under the leadership of Yiannis Zymvrakakis in West Crete, Panayiotis Koroneos in central Crete and Michael Korakas in East Crete. The central slogan of the revolution was “Union or Death”. The Sultan, faced with this dilemma, obviously chose the second-death to the Cretans. To this effect, he sent to Crete his best (i.e. most brutal) general, Mustafa Giritli Pasha, who organised an army of 55.000 fanatical Turks. Terrible battles broke out throughout Crete with great losses on both sides. The Cretans had no help from the Great Powers, which in this case maintained a clearly pro-Turkish stance. The only ones who strengthened their struggle as much as they could, were fellow Greeks from free Greece.

1866 The peak moment of the revolution was the Holocaust of Arkadi in November 1866, when the 900 Christian defenders of the monastery, realising that they had no hope of being saved, blew up its powder magazine, bringing death to more than 1.500 Turks. This shocking event fired important Philhellenistic demonstrations throughout Europe, but the governments of the Great Powers remained unmoved and, on top of this, they obliged Greece to cut off the aid to Crete.

1869 The revolution was extinguished with the Treaty of Paris and the Turks consolidated their domination over the island, although they were obliged to grant significant privileges to the Cretans, with the so-called Organic Law.

1878 With the opportunity given by the Russo-Turkish war, a new revolution broke out in Crete with the demand that Crete be declared an autonomous state paying taxes to the Sultan, but with a Christian governor. The Turks naturally rejected the demand and the revolution took on enormous dimensions, with spectacular successes for the Cretans. The revolution ended with the Agreement of Chalepa, which granted significant political and economic rights to the Christians. Among other things, Greek was sanctioned as the official language of Crete, the publication of newspapers was allowed, and Crete acquired a General Assembly to which 49 Christians and 31 Moslem members of Parliament were elected. Turkish oppression was steadily losing ground and the time was approaching when it would be completely thrown off.

1878 Amid the general chaos, a sensitive, educated Cretan, Minos Kalokerinos, from Iraklio, did the first excavations at the ruins of Knossos. His findings (mainly earthen jars) were donated to foreign museums and to the Friends of Education Society of Iraklio.

1886 The German archaeologist, Heinrich Schliemann, already famous for his excavations in Troy, showed interest in excavating at Knossos and tried to buy a large piece of land in the area. But the money the owner of the field was asking seemed a lot to him and he left, angry!

1889 As if is wasn’t enough for them to be ill-fated and barefoot under a powerful occupier, the Cretans argued amongst themselves! Such a civil political clash between the Cretan members of Parliament led to yet another revolution against the Turks, which the conquerors crushed immediately and which they used as a pretext to repeal the Agreement of Chalepa and to steep all of Crete in blood with indescribable acts of brutality. Europe continued to be unmoved.

1894 The English archaeologist, Arthur Evans, came to Crete for the first time and discovered that it was an unexplored archaeological paradise!

1895 A new revolution of the indomitable Cretans, which was also crushed by the indestructible Turks. Unbelievable new atrocities by the Moslems finally moved the Great Powers, who intervened and obliged the Sultan to ensure the Christians’ political rights by way of a sketchy Constitution, the so-called Memorandum.

1897 Not only did the Turks never put into practice the Memorandum which the Great Powers had dictated to them, but they also began to act with undisguised cruelty towards the Christians. An unrestrained mob of Turks in Iraklio began to kill Christians and to burn down churches, as in the bad old days. But those days had finally gone into the past. The Greek government intervened strongly, ignoring the pro-Turkish stance of the Great Powers. It sent warships and 1.500 soldiers to Crete to reinforce the new revolution that had spread right throughout Crete. The Great Powers sent their own fleets, which blockaded the Cretan coast in order to obstruct the dispatch of Greek reinforcements, set a 6 kilometre zone around Chania which they forbade the Greek forces to approach, and proposed the declaration of Crete as an Autonomous State. The rebels rejected the proposal and continued their struggle, demanding unification with Greece.

1898 The great powers decided to impose their own choice and took Crete. The English took Heraklion, the Russians RethymnonThe Great Powers decided to impose their own choice and they captured Crete - The English took Iraklio, the Russians Rethimno, the Italians Chania, the Germans Souda, the French Sitia and the Austrians Kasteli Kissamou! Greece was then forced to withdraw its forces. The Cretan rebels were forced to accept the plan of the Europeans, who appointed Prince George of Greece as governor of the Autonomous Cretan State and placed it under their protection.

1898 Whilst the English were establishing the new administration in Iraklio, an enraged Turkish mob poured into the city, slaughtered hundreds of Christians, set fire to houses and churches and proceeded to all kinds of barbarous acts. While the river of Cretan blood spilled over so many years left the Europeans unmoved, the blood of the 17 English soldiers, killed in this final outbreak of Turkish barbarity, was the straw that broke the camel’s back. The Europeans now realised what Turkish barbarity really meant, and they reacted strongly. They arrested and hanged the Turkish instigators and ordered the Turkish army to leave Crete immediately. On 2nd November, the last Turkish soldier left Crete. So, after 230 years, the period of Turkish occupation finally came to an end - it was one of the most nightmarish periods in Cretan history.

Autonomous Cretan State (1898-1913)

1899 1899 Prince George, the Supreme High Commissioner (something like king, that is) of Crete appointed a 16 member committee that prepared a draft constitution and proclaimed elections, which took place in an absolutely orderly fashion and which set up the first Cretan government, where a powerful political personality stood out - Eleftherios Venizelos.

1900 The English archaeologist, Arthur Evans, came to Crete again, bought a large piece of land in the Knossos area and, by systematic excavations which lasted for 31 years, brought to light the ruins of the Palace of Knossos.

1901 Prince George believed that Crete should continue as an Autonomous State, while the Cretan people as a whole, with Venizelos as their chief spokesman, sought unification of Crete with Greece. As was to be expected, they came into collision. Prince George sacked Venizelos from the government (as he was empowered under the Cretan Constitution) and things started to get hot again. They were difficult times for princes....

1905 With Venizelos as leader, around whom the most capable politicians in Crete and all the Cretan people were allied, the “Provisional Government of Crete” was formed in the village of Theriso.

1906 Prince George was forced to resign and his place was taken by Alexandros Zaimis, a person trusted by Greece, by Venizelos and by the Great Powers.

1907 The Cretan Civilian Guard was formed, which undertook to keep order and to protect the regime. The armies of the Great Powers were withdrawn from Crete.

1908-1909 As Austria had managed to annex (the diplomatic word for “grab”) Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Bulgaria East Romylia, with no international reaction, why should Greece not annex Crete with which, when it came down to it, it had the closest national and religious bonds? The Cretan members of Parliament, headed by Venizelos, proclaimed unification with Greece and introduced the Greek Constitution to Crete. The High Commissioner, Zaimis, who at that time was away from Crete, received an order not to return to the island, where a temporary coalition government was being formed. Greece, so as not to provoke international reactions, did not officially accept the unification. In fact, the Great Powers did not intervene, despite Turkey’s strong protests. When, however, the Greek flag was raised on the fortress of Firka in Chania, a detachment from the European fleet landed and took it down.

1910 Venizelos was elected Prime Minister of Greece. A brilliant politician and diplomat, he worked carefully in the direction of unification of Crete with Greece, and also of regaining Greek territory in Thessaly, Epirus, Macedonia, Thrace and the Dodecanese. He reinforced tacitly and very effectively Greece’s military strength and when he finally felt ready, he declared war on Turkey.

1912-1913 First Balkan War. Greece allied with Bulgaria and Serbia. The allies attacked the Ottoman Empire, put down all resistance and freed significant parts of their territories. By the Treaty of London, which ratified the new borders of these countries, Crete was at last unified with Greece. On 1st December 1913, the Greek flag was officially raised on the fortress of Firka in Chania.

Province of Greece (1913-present)

1923 Following the Asia Minor Catastrophe (the brave but unsuccessful attempt by Greece to free the very ancient Greek territories in Asia Minor from Turkish occupation), a large wave of Greek refugees came to settle on the hospitable land of Crete. By the Treaty of Lausanne, which regulated the question of population exchanges, all the Turkish minority in Crete (around 32.000 people) were forced to leave the island.

1941 The Battle of Crete. The German Staff, and specifically staff officers Gohring (chief of Luftwaffe) and Student (deputy chief of Luftwaffe) drew up the “Mercur” Plan for the capture of Crete. All day on 20th May, a cloud of 1.100 airplanes rained down German parachutists of the crack 7th Division. On the ground, they were “welcomed” by approximately 32.000 allies (English, Australian and New Zealanders) with 10.000 Greek soldiers (very badly armed) and the whole of the Cretan people who saw a foreign invader and ran amuck! Despite their terrible losses (4.000 dead parachutists and 170 crashed airplanes), the Germans captured Crete within ten days.

And Crete, fortunately, remains part of Greece to this day...

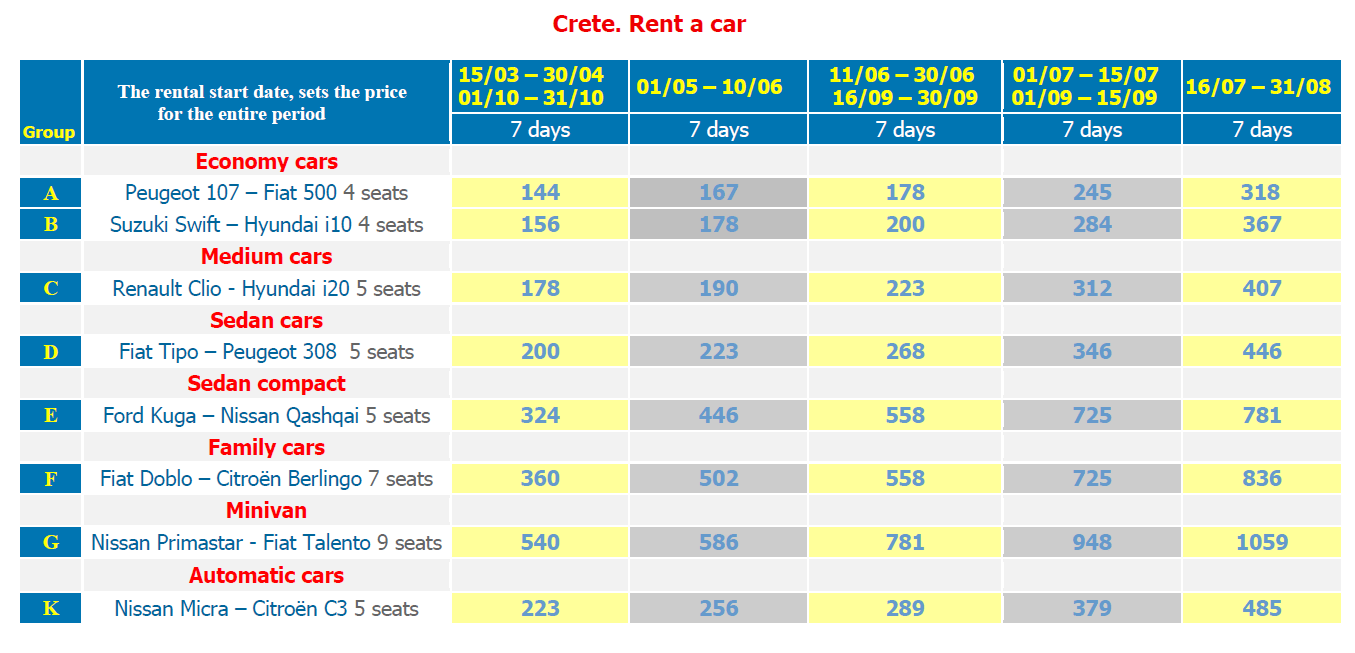

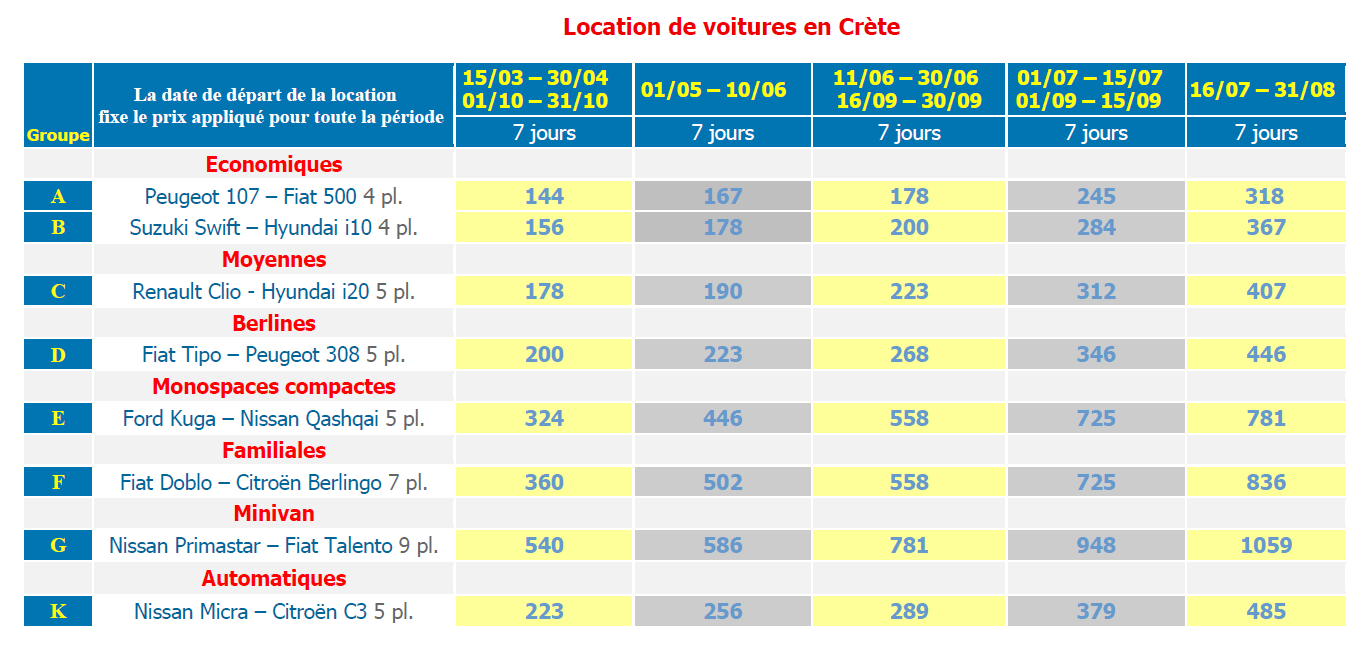

Rent a car in Greece: Crete (Heraklion, Chania, Rethymnon, Agios Nikolaos) – Athens – Rhodes – Corfu – Mykonos – Santorini – Thessaloniki – Preveza/Aktion/Lefkada – Patras/Araxos – Kalamata – Paros – Syros – Kos – Naxos – Lesbos – Thassos – Zakynthos/Zante